This book has a simple premise: “Unregulated capitalism is bad for women,” Kristen Ghodsee argues, “and if we adopt some ideas from socialism, women will have better lives.” Ghodsee is an ethnographer who has researched the transition from communism to capitalism in eastern Europe, with a particular focus on gender-specific consequences. “The collapse of state socialism in 1989 created a perfect laboratory to investigate the effects of capitalism on women’s lives,” she writes.

Less regulated economies, she finds, place a disproportionate burden on women. Women subsidise lower taxes through their unpaid labour at home. Cuts to the social safety net mean more women have to care for children, the elderly and the sick, forcing them into economic dependence. Ghodsee contends that without state intervention, the private sector job market punishes those who bear and raise children and discriminates against those who might one day do so. The government is better at ensuring wage parity across different groups than the private sector, and economies with more public sector jobs tend to have more gender equality, too. Women bear the brunt of capitalism’s cyclical instability, and are often the last to be hired and the first to be fired in economic downturns. They are paid less, they have less representation in government and, she writes, all of this affects their sexuality. The less economic independence women have, the more sexuality and sexual relationships conform to the marketplace, with those who are disadvantaged in the free market pursuing sex not for love or pleasure but for a roof over their heads, health insurance, or access to the wealth or status that capitalism denies them.

Ghodsee distinguishes between the “state socialism” of eastern bloc countries ruled by communist parties that restricted political freedom, and “democratic socialism”, where governments pursue socialist principles as well as having free and fair elections. She is not advocating a return to life as it was in Soviet Russia, but pointing out certain policies undertaken by eastern European countries under state socialism that could be successfully adopted by democratic countries. She addresses not only the question of sex but also imbalances in employment, leadership and parenting. Policies informed by socialist ideals such as a government jobs guarantee, quotas for female or gender nonbinary participation in corporate leadership and guaranteed childcare allow women autonomy, independence and, she contends, a happier sexual life.

“Socialists have long understood that creating equity between men and women despite their biological sex differences requires collective forms of support for child rearing,” she writes. In East Germany, for example, the state supported integrating women into the workforce with policies that subsidised housing, children’s clothing, groceries and childcare. This support also meant that women could more easily consider having children without waiting for marriage. By 1989, 34% of all births in East Germany were to single parents. After German reunification, the end of these subsidies resulted in a “birth strike”: the fertility rate in former East German states fell by 60%.

Her argument that socialism leads to “better” sex is harder to substantiate. So many cultural factors play into a sense of sexual satisfaction, and certain eastern European countries reporting higher rates of female orgasm during the cold war than the US or West Germany is not necessarily correlated to socialist policies. What is true, however, is that less inequity decommodifies sex, and undermines the odious theory of “sexual economics” whereby women keep the “price” of sex high by denying it. As Ghodsee points out, “in societies with high levels of gender equality, with strong protections for reproductive freedom, and with large social safety nets, women almost never have to worry about the price their sex will fetch on an open market.”

Ghodsee also argues that the cold war, and the global rivalry between capitalist countries and state socialism, served to keep capitalism in check. In the 30 years since it ended, such countries as the US and Britain have seen unfettered deregulation, privatisation, cuts to the social safety net and a sharp rise in inequality. The effect on women has been devastating. Wages have stagnated, and more of the workforce has been thrown into the instability of the gig economy (which, in the US, also means less access to healthcare). In the US, at least, birth rates have fallen. The reasons are unclear, but the lack of state support for working mothers is probably a factor.

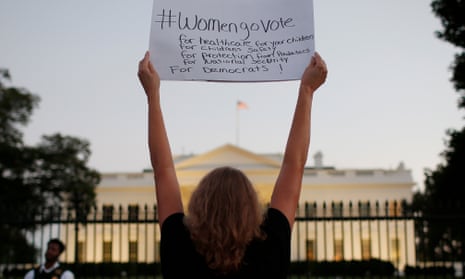

Ghodsee’s book could not have been published at a better moment. In many wealthy countries, people are getting married later or not at all, they are having fewer children, and a higher percentage of those children are born to unwed parents. The conservative response to this realignment of sexual relationships and family structures is to lament the decline of the patriarchal family. The socialist response is to propose government institutions that better address the reality of the societies we live in. Policies like subsidised childcare, universal healthcare and mandatory parental leave mitigate the effects of having children on a young woman’s career, and offer greater support for single parents. They allow women in abusive relationships greater freedom to leave. They enable sexual freedom. There are many reasons to revisit socialist policies in a time of widening inequality, but a feminist perspective offers some of the most powerful incentives. As Ghodsee notes, younger women are far more likely to vote for progressive candidates, and benefit most directly from progressive ideas. The cause of sexual freedom has also become a unifying thread in women-led political movements. The election of Donald Trump and the confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh to the supreme court have given a heightened sense of the correlation between tax cuts, cuts to the social safety net, and a politics of sexism, including disdain for a woman’s autonomy over her own body. Ghodsee spells out the capitalist incentives behind policies that are so often disguised as “culture wars”, and ends her book with the exhortation to “push back at a dominant ideology” that confuses social bonds with economic exchange: “we can share our attentions without quantifying their value, giving and receiving rather than selling and buying.”